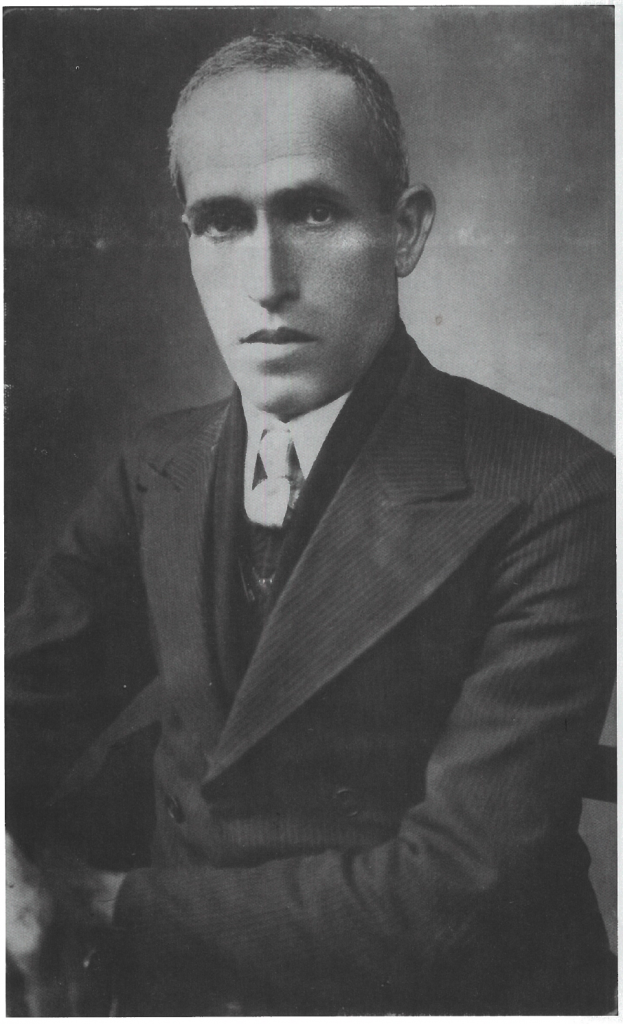

Mola Elias (Eliyahu) Kashi-Malak was a leader of the Jewish communities of Mashhad and Daregaz in the early-to-mid 20th century. He was born in the city of Mashhad (north-east Iran) in the month of Iyar 1892 to Mousa (Moshe) and Dina Kashi. Mashhad was a city in which the Jewish community had suffered much persecution in the 19th century. Most famously, in 1839, a pogrom which took place in Mashhad led to the death of dozens of its Jews and forced conversion to Islam for many of the survivors, most of whom would continue to practice their Jewish faith in secret. The story of the Mashhadi Jewish community is both rich and long, and we cannot do it proper justice in this short article. However, by learning a little bit about Mola Elias’ life story, one can get a glimpse into the sacrifice that many of the Jews of that area in Iran made. While they suffered much persecution and hardship, they nevertheless ensured that they would be able to faithfully pass their Jewish heritage to the next generation.

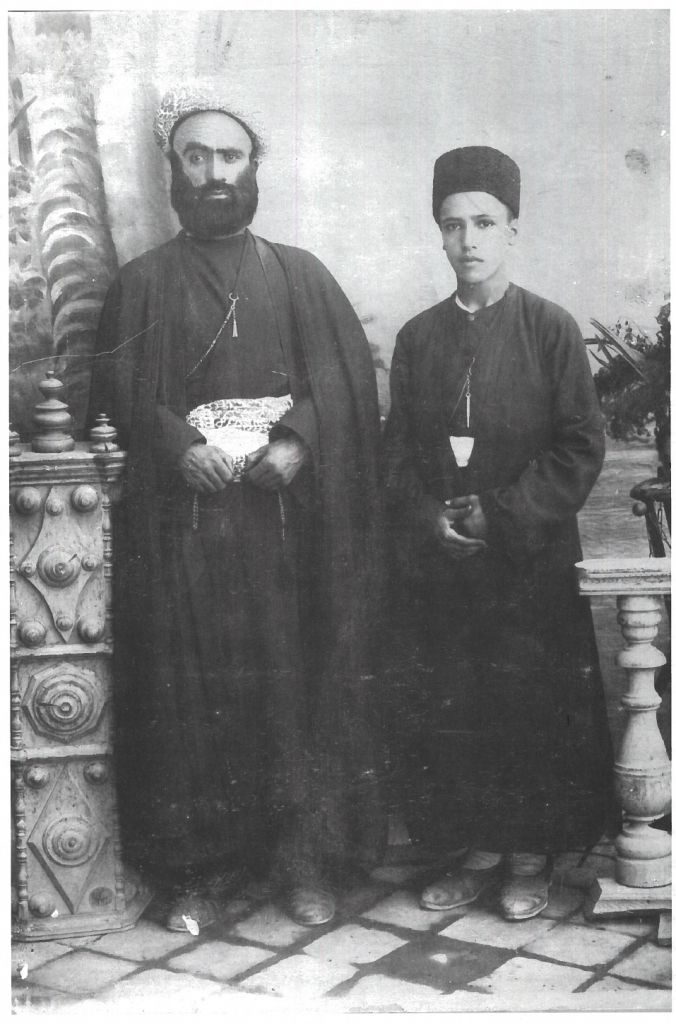

Born in Mashhad to a family which originally came from Kashan (as the last name Kashi suggests), Mola Elias Kashi-Malak would spend most of his life in the nearby city of Daregaz, which like Mashhad was also situated near the border with Russia (today Turkmenistan). Early in his life he was involved in the textile business and was a landowner in Daregaz, but when his father passed away in 1920 (when Mola Elias was 28), he decided to devote his life to serving his community, and he soon became the city’s Rabbi. As was common in other Iranian cities in the 19th and 20th centuries, the city Rabbi (or ‘Mola’, as most were known), was not only responsible for conducting marriages, divorces, and giving sermons at the local Synagogue. Mola Elias was also responsible for being the Ba’al Koreh, Mohel, and Shochet for his community.

Formal Jewish education in 19th century and early 20-century Iran was rare, and Mashhad was no exception. Mola Elias would get the majority of his education at home and from the local Synagogue. By the time he was growing up in the early 1900’s it was getting a bit easier to openly live as a Jew in Mashhad (for the decades before many had to hide their Jewish practice) and Mola Elias was even able to go to a small school run by Mola Hodadad ben Yekutiel, who was originally from Yazd. It’s not clear if Mola Elias’ father, Mousa, was also a Rabbi, but he was obviously a Talmid Hacham. Recently, writings of his were found among the personal items of one of his grandsons in New York. They include notes which he made on the margins of a classic 17th century Halachic work known as the Peri Hadash. From both the quality and quantity of his notes it’s evident that he had a very high level of Halachic knowledge, particularly within the topic of Shechita. Those notes are currently in the process of being published by other family members.

Mola Elias Kashi-Malak was different from other Persian Rabbis of his time in that he was relatively wealthy, whereas the vast majority of the other Hachamim/Molas led lives of financial difficulty. This not only allowed him to serve his community as a volunteer and not take any payment for his services, but also led to him having very good relationships with the local non-Jewish authorities. He would often organize social gatherings at a large park that he owned where he would invite the local politicians and police officers; he even donated a building which he owned in the center of the city to the local Government, and he rented the building which housed the local prison to the police department as well. In fact, Mola Elias’ original last name was only ‘Kashi’ – the word ‘Malak’ which was later added to his last name is the Farsi word for someone whose occupation is Real Estate.

These connections which had developed were very useful when Mola Elias had to save members of his local Jewish community from various threats and incidents (which were unfortunately not rare). One example was in the year 1924, at a time when many people (including Bucharian Jews) were fleeing from the new Communist government which was coming to power in Russia as a result of the Bolshevik revolution. One such family were distant relatives of Mola Elias, a young couple with a 5-year old daughter who were fleeing on horseback to Daregaz by way of Turkmenistan. When the family never arrived, Mola Elias (together with other relatives in Russia) began searching for them on both sides of the border. He was soon notified by authorities in Turkmenistan that they had found the bodies of a couple matching the same description, but that the little girl was missing. Soon after there were sightings of a family of Muslim gypsies who were riding on new horses in the area and in possession of a little girl. Immediately authorities on both sides of the border started looking for the gypsies until they were captured on the Iranian side of the border and detained.

The murderers denied any responsibility for the murder of the young couple and claimed that the little girl was theirs. Due to his excellent relationship with the local authorities, Mola Elias, who was only 32 at the time, immediately went to visit the gypsies and their “daughter” in the prison and noticed that she looked very similar to her deceased mother (who had known), but for the authorities his opinion was not going to suffice. Mola Elias went home and came back to the prison with a pair of Shabbat candlesticks, a Chumash, and a set of playing cards. He told the officer that he could prove that the little girl was Jewish and did not belong to the Muslim family. He first lit the candlesticks on the officer’s desk and asked the little girl if they reminded her of anything? She responded that her mother would light candles every Friday night, and she even proceeded to mimic her mother’s hand motion when she lit the candles. Mola Elias then showed the girl the Chumash (Torah) and asked her what it was? She responded that her father would read that week’s Parsha out of a book just like that one every Friday. He finally showed her the playing cards, and the girl said that her parents would often play certain card games that were very common among Jewish families living in that area of Iran.

The police officer referred the case to the local Governor, who would have the final say. Word soon spread among the Muslim residents of Daregaz that the Jews were trying to “steal” a child from a Muslim family. Mobs surrounded the street between the police station and the governor’s office (which were adjacent) and everyone was eagerly awaiting the final ruling. People were lined up on both sides of the street as police officers marched the Gypsy family (who had dressed the little girl in their attire) from the police station to the local Governor’s office. In the ensuing tense atmosphere, an Islamic thug grabbed Mola Elias by the coat, pointed a dagger at him and threatened him to leave the girl alone. Mola Elias responded that the thug was welcome to kill him if he wanted to, but the girl was Jewish according to the law and belonged to her family, not to the gypsies. After a few hours, Mola Elias received the ruling he was waiting for – the girls indeed belonged to the Jews. He brought her home (with a police escort) and triumphantly declared “The girl is ours!” In order to calm the tensions in Daregaz, he immediately sent her to Mashhad to live with relatives. The little girl later married one of Mola Elias’ family members (Habibolah Kashi), and she made Aliyah to Israel together with him in 1949.

Another incident took place a few years later, sometime in the year 1927 (or 1928). Several human skulls were discovered under a home which used to belong to 2 Jewish brothers, resulting in a vicious blood libel against the Jews, with some local Muslims claiming that the former owners had killed Muslim children to use their blood in the baking of Matzot for Pesach. Mola Elias, together with other community members, immediately started working to protect the community from the impending riots and combat the lies which had been spreading. They enlisted the assistance of a local Islamic elder who was known to be empathetic towards the Jewish community, and they asked for his assistance. He agreed to help, and at the same time Mola Elias also enlisted the assistance of communal leads from Mashhad.

In the meantime, in order to quell the anger of the mob in Daregaz, local authorities arrested not only the 2 brothers who owned the home, but also more members of the Jewish community, including some of Mola Elias’ colleagues who were Rabbis themselves (such as Mola Rahmat Hematian). Mola Elias himself was saved from imprisonment due to his warm relationship with the local authorities (it also did not hurt that he owned the actual building which housed the prison!), and he used his freedom to deliver kosher food daily to the Jewish prisoners. He was able to also convince the local authorities to send the human remains to Mashhad for analysis, confident that his community was innocent of the charges. During the month that it took for the results to come back from Mashhad, the Jews of Daregaz remained locked in their homes, fearing for their lives. But when the report came back from Mashhad that the human remains were 150 years old, and belonged to adults and not children, another crisis was averted and the Jews were safe again.

Finally, a few days before Pesach in the year 1936, the central Government in Tehran sent an order to the local authorities in Daregaz and two other nearby cities demanding that their local Jewish populations be expelled and exiled within a few days. After the local community leaders (Jewish and non-Jewish alike) met at Mola Elias’ home, urgent telegrams were sent back to Tehran insisting that there must have been some mistake, and asking for mercy. It was soon revealed that a local Muslim merchant (who wanted to do away with his competition) had lied to the authorities in Tehran, claiming that the Jewish community was spying on behalf of Russia. The decree was soon rescinded and the Jews of Daregaz were safe. Once again, Mola Elias Kashi-Malak was able to use his excellent relationships to help his community; however, this last blood libel proved to be the final straw for much of the community. The majority of the Jewish residents of Daregaz would soon move to Mashhad or Tehran. At its height, the Jewish community of Daregaz had numbered approximately 240 families. By 1966, there were approximately 20 Jewish families left, and today there are none.

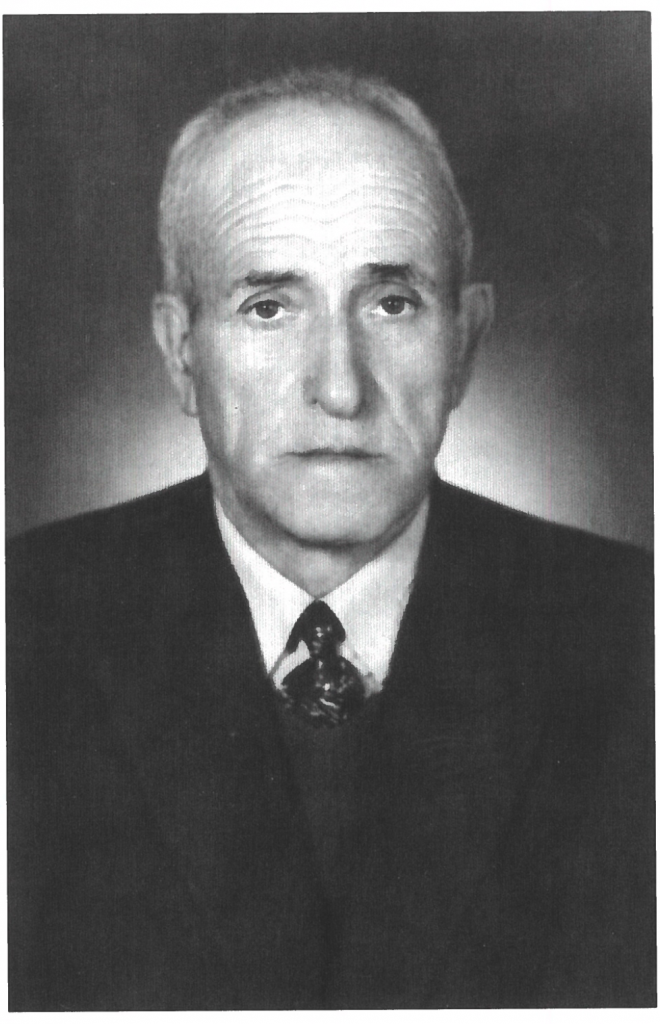

Mola Elias Kashi-Malak married twice. His first wife, Esther, passed away in 1933 at the age of 34 from a serious illness. He soon remarried to Devorah, who passed away in 1988. He was blessed with many children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, who live today in either New York or Israel. Mola Elias spent the end of his life in Tehran, where he passed away on the 23rd of Iyar 1966 (5736) at the age of 74.

The article and pictures above have been taken from a book that was printed in Israel in 2002 about Mola Elias Kashi-Malak and Mashhadi Jewry. The book was published by Mola Elias’ son, Yehuda Haklai. I was able to interview Mr. Haklai about his father before writing this article in August 2022. He is today close to 90 years young. – AS

Recent Comments